“The gods smelled the savor,

the gods smelled the sweet savor,

and collected like flies over a sacrifice.”

-Epic of Gilgamesh, Tablet XI

In the ancient Mesopotamian story of the Epic of Gilgamesh, the great flood sent to destroy mankind has disastrous consequences for the gods. A common view of ancient sacrifice is that you were, quite literally, “feeding” the god you sacrificed to. So when Enlil sent the flood to wipe out noisy1 humanity, he inadvertently cut off the gods’ food supply, and by the time Utnapishtim2 offered his post-flood sacrifice, the gods were ravenous, gathering over it like flies.

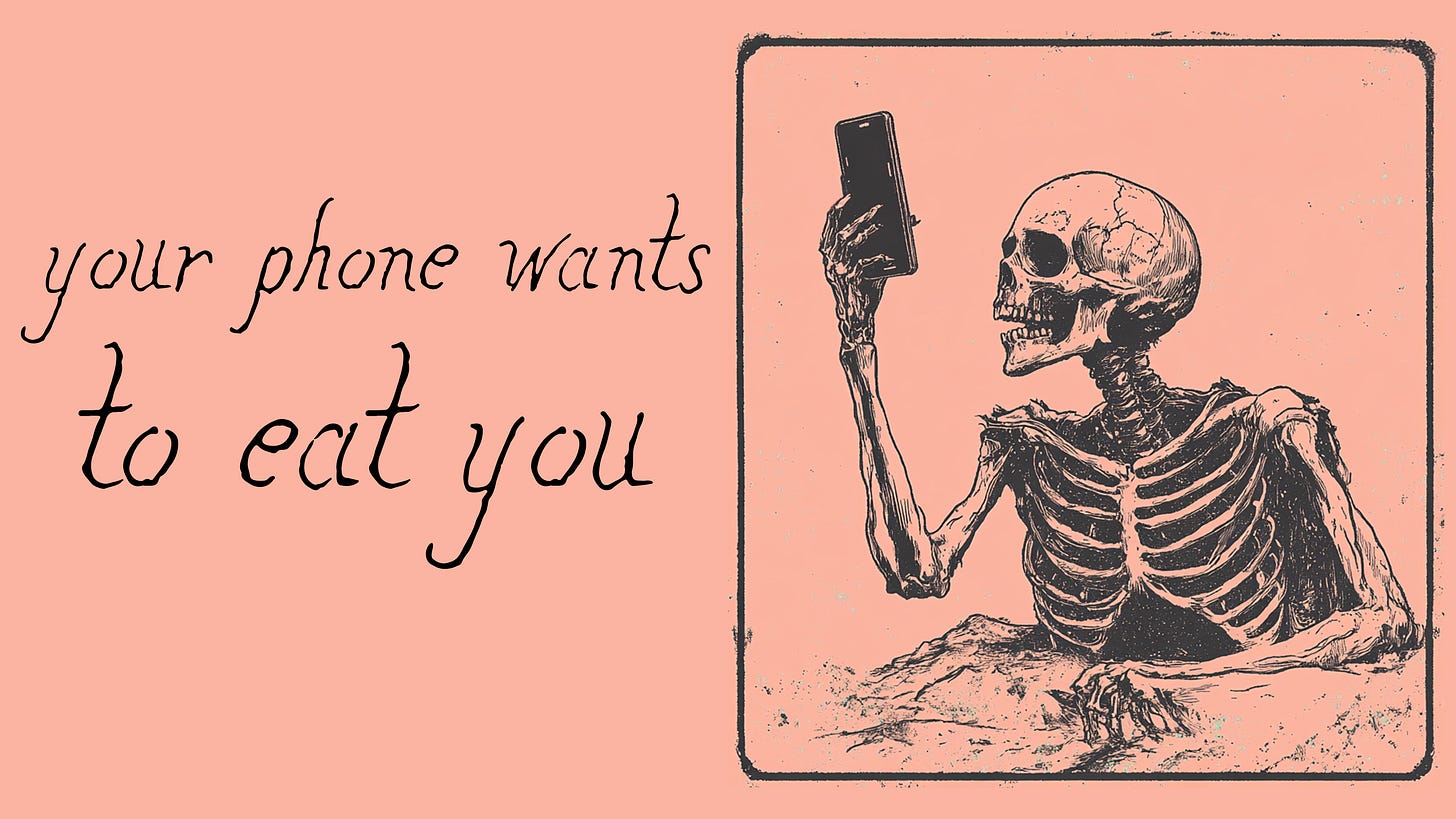

I’ve previously characterized social media algorithms as “dark gods,” and today I’d like to both double and triple down on that personification. The transactional view of the ancients is a perfect encapsulation of our interactions with social media, merely re-imagined in digital form. The gods ruled aspects of everyday life, seasons and weather and harvest and famine, and if you placate them with the appropriate oblations, they will order those things in your favor. Displease them, and you risk their wrath.

Our world has gone digital and the gods have adapted. The mantra of “the internet is not real life” no longer applies because what is stated online determines a disconcerting proportion of real life. Mark Twain’s warning about how much faster lies travel than truth looks downright prophetic in a time where someone can just put “🚨🚨BREAKING🚨🚨” before something they made up and watch thousands of people blithely amplify the lie. Accountability is irrelevant to the shameless and the shameless are afforded intractable power in a world guided by engagement and advertising (commercial or otherwise).

But this is the way of the new gods. They’ve found something more precious to us than our livestock or agriculture; they’ve learned to harvest our time. Over the last few years, every social media feed has followed the model of TikTok3 in centralizing and prioritizing the algorithm as the primary means of delivering content to maximize time spent on the app. The content is free, because you are the product. We are the sacrifice, burning hours and hours of our lives for the brief reward of distraction and amusement, which the new gods are more than happy to provide.4 And before we know it, we’re better than a devote at their altar; we’re an addict. A transactional relationship isn’t based on love, worship, or fealty, so like any technological innovators, the gods have realized that compulsion is better than coercion. They consume us one piece at a time, without killing us, so the meal lasts as long as we do. They drive us into little holes, little reality-deprivation chambers where the only light is our phone screen, and the only joy is our feeds.

“Feed.” What a fittingly ironic term for it.

Before, humanity was their supply chain, but now it’s also their mouth. We not only bring the offering to be consumed, we consume it on their behalf. Our attention spans have become fleeting, and our desire for instant gratification is devolving from the patience of two-day shipping to the onset of immediate drone delivery. Instead of the algorithm conforming to us, it now molds us into conforming to it. Instagram taught us how to display a curated image and judge our worth by attention. Facebook taught us how to vocalize the right opinions that incentivize the maximum atta-boys. Twitter taught us how to remove all that pesky nuance and context from our thinking and phrase things in the most direct, incisive way possible. TikTok gave us a lottery for fame, showed us how anyone could go viral overnight if the algorithm smiles upon you. And all of these platforms taught us that we must add our voice to every conversation, always. “Can I interest you in everything, all of the time?” Indeed, the new gods have made us in their image.

And I hate it. I mean I really hate it. I’ve hated it for years and it’s only made worse by hating it and not doing anything about it. I’ve always had excuses to stay, legitimate excuses, mind you; during my freelance days, a considerable chunk of my clientele came via social media. Today, social media plays an essential role in self-promotion, brand awareness for artists like myself, keeping in touch with friends from out of town, and in all sorts of other positive things. I don’t like dealing in absolutes so I would never say it’s all bad for everyone, but I do think that even with the notable good, it might be (almost) all bad for me. I don’t like what social media has done to my attention span, to my engagement with the world, to the management of my time, to the intractable fomo that assaults me anytime I’m away from it, to the feeling that I need to be constantly plugged in and updated and in touch and informed on everything happening everywhere all the time. I hate how compulsive scrolling has become, how addictive my feeds are, and the countless hours I have wasted scrolling and scrolling and scrolling and scrolling. Of all the shame that will be laid at my feet when I face God, how much of his time I offered to idols may be my chiefest sin.5

There is a reason ancient Christians came to view many of these voracious deities as demons. And I have no qualms anymore about employing the term “demonic” alongside other descriptors of our social media landscape. I do not mean this as pearl-clutching superstition; I have no fear that little red spirit monsters are going to magically possess our children and turn them into Marxists. In fact, I don’t feel the need to appeal to any supernatural “possession” at all; the addiction to scrolling is possession enough. The demonic spirit I’m talking about can’t be exorcised, only deleted, but the fact that it’s a technological evil doesn’t make it any less spiritual of a problem. And while I believe there are some technological solutions, the true antidote to this chaos is, first and foremost, spiritual.

I've always balked a bit at the many tales of the Desert Fathers battling demons (a common occurrence in ancient monastic hagiographies). It always struck me as rather silly and superstitious, a sort of hyperbolic way for ancient authors to personify the strident seriousness with which these ascetics carried out their calling and tell a more interesting tale than that of an emaciated elder meditating 20 hours a day. But I’m increasingly coming to believe this personification might be the exact right approach to our present situation. If history and present politics have taught us anything, it’s that providing an “enemy” to focus on is a powerful and effective tool for spurring action. I think, perhaps, employing the melodramatic language of setting these algorithms in opposition to our very humanity can aid in battling the feeds that wish to consume us and might even help us recognize the genuine spiritual warfare present within. Or, to put it more hyperbolically, perhaps giving a name to these “new gods,” as I have done, will help us recognize them for the demons they have always been.

In war, you look to strategists who know the battlefield. For Christians, these warriors are the monks. I’m not suggesting we all leave our homes and families and flee to the desert, but we can “retreat” from the world in a meaningful way. A life lived online is as malleable as code and the world as a whole is currently suffering from that determination of reality. So the solution isn’t to run away but to return to the real world. The desert we can flee to is just…living offline. I don’t need to go to a cave; I just need to put my phone down.

Paul Kingsnorth has an uncanny ability to articulate exactly what I’m thinking. I don’t know who let him into my brain or what he’s doing there, but from repeating the same conclusions from a Facebook post of mine from a few years ago in his recent lecture to articulating a section of this current essay far better than how I wrote it, he’s got my number. I initially wrote a few paragraphs on how St. Anthony kicked off monasticism and how primitive Christianity conquered Rome, but as Kingsnoth’s phrasing is both more concise and more pleasing, I will simply quote him at length:

“Seraphim Rose saw:

Christ is the only exit from this world. All other exits - sexual rapture, political utopia, economic independence - are but blind alleys in which rot the corpses of the many who have tried them.

What a mystery. What a weird, frightening, exciting mystery: that only through death can we achieve life. That he who tries to save his life loses it, and he who sacrifices his life saves it. That God’s wisdom is foolishness to the world, and that Christ has called us out of that world, to a place where we will be hated precisely because we walked away from it. The more you meditate on this, the more impossible it seems. Impossible and ridiculous and obviously true. Sometimes this whole 2000-year-old faith seems like a living koan. Chew on this until you are enlightened. Keep walking.

Christ allows the authorities to kill him, without resistance. His helpless and agonising death sparks a global revolution which is still playing out.

St Anthony gives away everything he owns, runs off to the desert and holes himself up in an unused tomb. His certifiable behaviour creates Christian monasticism by accident.

Thousands of ordinary Christians allow the Roman authorities to burn them alive, feed them to lions, crucify or impale them in public. They do not resist their fates, and they often die smiling. Their sacrifice ends up Christianising the entire empire.

Other ordinary Christians share everything they own, give away the rest, and tend to the sick and dying even if it kills them too. Their sacrifice of love spreads their faith across continents, without the need for either missionaries or state support…

…There are many more such stories, and they all illustrate that living paradox: that only through sacrifice does Christianity ever flourish. This kind of sacrifice is not ‘giving up’, and neither is it ‘doing nothing.’ Do we think that St Anthony or St Francis were ‘giving up’? On what? On the world, perhaps; but not on God or on humanity. Quite the opposite. By walking towards God they made themselves more fully human. They made themselves more able to serve the world than someone who is immersed in it.”

The anxiety around “giving up” captures the fear of “unplugging” so poignantly. To leave the feeds feels like abandoning something, like ignoring an important conversation, like missing out on something meaningful. And much of it comes from a good place; I want to keep up with the news and be an informed citizen so that I can do my small part in working for a better world. But the truth is, when it comes to so many of the stress-inducing headlines I feel a compulsory need to keep up with, I have no real power to affect those issues at a macro level. The change I want to see is beyond my power. I cannot make Americans care about truth again, I cannot make social media companies care about mental health more than profit, and even if I had the power to attempt an impact, what makes me think I wouldn’t just make things worse? I can barely keep myself from compulsively tabbing over and checking Facebook as I write this article; with logs as big as that in my face, what good would come from picking at specks? The solution, the only hope, is a bottom-up solution, not a top-down one. As Kingsnorth, again, expresses my thoughts better than I could ever hope to:

Well, all I can say is that my intuition points me hard towards all of these stories and many more like them. What is the ‘solution’ to our modern ‘problem’? For a start, it is to stop thinking like that, because that is Machine thinking. We do not have a ‘problem’ that can be ‘solved’ by politics or war or top-down civilisational projects. We just have a repeat of a very old and familiar pattern: a turning-away from God, and thus from reality. This ‘problem’ is only ever ‘solved’ by turning back again, and societies can’t do that. Only people can, one at a time.

So today, I’m doing something I’ve wanted to do for years and leaving. Not completely, not forever, I’m not outright deleting my accounts or drowning my computer, but I’m going to make a concerted effort to log off. I’m going to try being a monk for a bit. I haven’t taken any vows; I’m a novitiate. I’m inquiring. I’m living by the rules of the order to discern if this life suits me. I want to do my best to focus my energy where I can make a difference - in my life, in my community, in my own soul. I doubt it will be easy to unplug; I’m fleeing from habits I’ve spent the last decade cultivating. But I think it’s time.

I have grand ideas for expanding this personal endeavor into an anti-algorithm art project. I thought I might try to launch it with this article, but the more I worked on it, the more I realized it needed a beta-testing phase. If I’m going to try and follow the model of the monks, I can’t begin with expectations of a movement. Those first monks didn’t run off to form specific communities, they just left. They found a cave, they prayed their prayers, and they surrendered the rest to God. Like Kingsnorth so eloquently stated, the only hope of a solution is enacted by people one at a time, so my first contribution to those efforts has to be me.

So this is my hope. I want my time and energy and concentration to be offline. I’m tired of being digital. I hate how much of my art and career still depends on a social media presence. I want to be like St. Anthony, who basically said “if you need me, come find me in the desert.” I miss wandering down the road to find people, taking the ten minutes to walk to someone’s door and knock rather than the (admittedly, more efficient) impersonal text to see if they’re home.

The goal is not to be anti-social or communicate less with people.6 The goal is to get back to more meaningful communication. This has actually been one of the joys of discovering Substack. This publication has allowed me to express and explore ideas in a way that feels more like speaking with interested parties and less like shouting into the void. I love how the comments on here, or the replies to the email notifications, or the phone calls prompted by my posts, have felt direct, personal, genuine, not motivated by clicks or clout. While I’m pulling back from Facebook, Instagram, and elsewhere, Substack, at least for the moment, feels less like posting a status and more like actually saying something, and as long as it serves that function, I’ll stay active here.7 The goal of retreating is not to hide myself from humanity but to starve these false gods.

So that’s the plan. If you need me, email me, call me, or come find me. Hopefully, I’ll be offline.8

And those who do, please pray for me. I doubt they’ll let me go without a fight.

In the Akkadian version of the myth, this is actually the motivation for the flood; there are too many humans making too much noise, and it prevents Enlil from sleeping well.

The “Noah” of this story.

I began this essay last year but as I sit down to finalize it, it’s currently January 18th and Tiktok is set to be banned in the United States tomorrow (though soon-to-be president Trump seems to be indicating he will work to reverse it? Even though he spent a good bit of his first term trying to enact this very ban?). I thought about dedicating a section of this essay to the discourse around that topic but realized I actually have very little to say. I understand the arguments regarding free speech or small businesses or how “national security” could be so easily misused to infringe on our rights but honestly, as much as I enjoyed the app, I think Tiktok is a net bad for us and I’ll be glad to see it gone, if it goes. I deleted it a few years ago and my brain is better for it.

And with generative content on the horizon, soon their excess will be infinite.

By volume, at least.

I also do have some obligations to post about film festivals and the like, so I’ll log on to do so when duty calls. Otherwise, contact@bennty.com is the best email to reach me if you don’t have my number.

Not to mention my “feed” here is primarily fascinating and edifying articles that make me want to read rather than scroll.

I feel that I need to clarify I’ve been planning this exit for some time and was even at one point planning this as my New Year’s post. I mention this because I’ve seen a lot of people leaving Facebook or Instagram out of protest for some of their policy changes in light of the incoming administration, and while I think people leaving those platforms is probably good for their health, I did want to make it clear my reasons for leaving are unrelated to the current trend.

I'm happy to say I've mostly disengaged w social media but moreso bc I don't care what anyone else is doing. I'm glad you're at least continuing with Substack, brother, bc I just paid for this subscription! XD Jk I've really valued digging into your deeper thoughts after consuming and collaborating with your art all these years. I'll stay over here on Tumblr: it's like a time portal into when the internet was slower and more anon with no way to make money. Jk, I know looking for another app to scroll is the opposite of your point of this article, but it's at least lacking in snarky political fights and instead abundant in feather-softcore goth porn (at least mine is).

I’ve been off X and Facebook for the better part of a year now. Accounts deleted. I have to say, I really enjoy not knowing what’s going on in those spaces. It’s just much better for my mental health, and my productivity. 🙂

I wish you well in your battles!